- S.D. Eibar ready for maiden La Liga outing

- SD Eibar stengthen ahead of debut La Liga season

- Can ‘Super Mario’ live up to expectations in Madrid?

- MAN IN THE GROUND – Brentford 0 – 4 Osasuna

- Historic Basque derby welcomes S.D. Eibar to La Liga

- Munich to Madrid, via Brazil – Tony Kroos

- Rakitic in Spanish Switch

- Can Spain find redemption in Rio?

- Viva Espana! A season of redemption for Spanish football

- From the old to the new: who can fill the void in years to come for La Roja?

The Mestalla – Home of Valencia CF

- Updated: 2 October, 2011

By Chris Clements

With its precipitous stands and mighty roof, the Mestalla cuts an unmistakable figure in world football. It oozes class and atmosphere and when full, scares the hell out of the opposition and their travelling support.

Alright, it dates from an era when supporter comfort was practically zero, but back then it was simple… going to a football match was just that, you watched the match.

In 1923, Valencia purchased a plot of land just to the north of their existing Campo de Algirós, close to the Mestalla drain. Club President and architect Francisco Almenar Quinzá designed the stadium, the first phase of which consisted of an uncovered terrace of 10 rows around two sides of the pitch.

The new stadium, with a capacity of 17,000 opened on 20 May 1923 with a match against Levante and staged its first international match 14 June 1925 when Spain beat Italy 1-0.

The improvements to the Mestalla continued and in 1926 work commenced on a new grandstand and additional work to the final end terrace, which increased the capacity to 25,000.

It was now one of the premier stadiums in Spain and because of its convenient location, equidistant between Madrid and Barcelona, it became a popular, neutral venue for the cup final.

The city of Valencia and the club were particularly badly affected during the Civil War. The ground was used as a camp for political prisoners and by the end of the war, stripped of all usable material, the Mestalla was derelict.

The club immediately set about rebuilding the stadium as all of the wooden terracing had gone and so had the roof of the grandstand. The club played its first post-war match at the Mestalla on 18 June 1939, which by they had a capacity of 22,000.

The 1940’s saw the club’s first golden era with 3 league titles and 2 wins in the cup. On the basis of this success, club president Luis Casanova was keen to further expand the Mestalla. In 1950, the club spent 7 million pesetas on acquiring land that adjoined the stadium.

Architect Salvador Pascual Gimeno designed the new lay out and work started on building larger terraces to the north and south of the ground.

In 1954, Gimeno began work on a replacement for the main stand and what a replacement it was! Holding 12,000 over two tiers, the striking feature was a cantilevered roof that was daringly high and deep for the 1950’s.

Flanking the roof are two towers that used to house the stadiums media facilities.

Development continued until the end of the decade, with the east side developed to include a slab-like anfiteatro, taking the capacity to over 50,000. Floodlights were added in March 1959.

In 1969, the club voted to change the name of the Mestella to honour their inspirational President Luis Casanova. So for the next twenty five years, the stadium became known as the Estadio Luis Casanova.

Casanova was overwhelmed and admitted to not being entirely comfortable with the gesture. In 1994, in his eighty-fifth year, he requested that the stadium revert to its original name.

The Estadio Luis Casanova underwent its next phase of redevelopment in 1978, when in preparation for the 1982 World Cup, architects Salvador and Manuel Pascual came up with an ingenious idea to increase capacity.

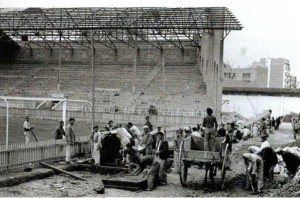

As the stadium could not expand outwards or upwards due to the close proximity of the neighbouring buildings, the pitch was excavated in order to build a new lower tier.

The first few rows of all the existing stands were also removed and in its place, several metres lower, went 20 rows seats. Still in place today, the back 10 rows are covered by extensions to the existing stands.

This mammoth operation bought its reward, as Spain played their first three matches in WC’82 in front of a packed Estadio Luis Casanova. With additional seating added to other areas of the stadium, the capacity remained at 50,000, but with 33,053 seats

In the summer of 1992, the stadium staged ten matches during the Olympic football tournament, including all of the Spanish national teams’ games up to their final success in Barcelona.

In mid 1990’s the club bought land that had become available around the Mestalla and formed plans to add another tier to the three open sides of the stadium.

Starting with the south grada in 1997 and finishing with the north grada in 2001, the stadium was turned into a 53,900 all-seat arena at a relatively reasonable cost of 24 million euros.

With money arriving by the lorry-load thanks to their relative success in the Champions League, Valencia genuinely thought they could consistently challenge the established hierarchy of Spanish football. They had the players, but they believed they needed a larger stadium.

In November 2006 the club unveiled plans to move from the Mestalla to a new stadium in the north west of the city. The stadium would seat 75,000 and cost of 344 million euros.

Work began in August 2007, but Valencia did not make that season’s Champions League. No Champions League means no lorry-loads of euros and with the world financial crisis looming, the banks started to get twitchy.

A further failure to qualify for the Champions League in 2008-09 saw the clubs debt rise to over 500 million euros and when in the summer of 2009, they defaulted on several payments to the construction company, worked stopped on the new stadium.

The site has lain empty ever since and the project has been all but abandoned.

So where does this leave the club? The debt has reduced, but 200 million euros is still a crippling amount to owe. With little chance of selling either the Mestalla or the building site-cum-stadium, the most likely outcome is that Valencia must continue to develop or buy players on the cheap and sell them at a profit.

A cautionary tale, that leaves Valencia a million miles away from their aim of a decade ago.

To read more on the footballing stadiums of Spain, visit Chris’s excellent site Estadios de fútbol en España

Follow @icentrocampista

You must be logged in to post a comment Login