- S.D. Eibar ready for maiden La Liga outing

- SD Eibar stengthen ahead of debut La Liga season

- Can ‘Super Mario’ live up to expectations in Madrid?

- MAN IN THE GROUND – Brentford 0 – 4 Osasuna

- Historic Basque derby welcomes S.D. Eibar to La Liga

- Munich to Madrid, via Brazil – Tony Kroos

- Rakitic in Spanish Switch

- Can Spain find redemption in Rio?

- Viva Espana! A season of redemption for Spanish football

- From the old to the new: who can fill the void in years to come for La Roja?

Catalonia is not Spain! – Nationalism, separatism and the greatest rivalry in world football

- Updated: 12 April, 2012

Action Images/John Sibley

Action Images/John Sibley

Not many countries have constitutions which refer to several nations and peoples within a single sovereign state. Whilst many nationalists would like to consider their nations to be unique, in Europe only Spain has so finely worded a charter.

When the post-Franco constitution was drawn up in 1978, the question of addressing Spain’s significant regionalism was hotly debated. This was a nation which had, of course, been engaged in a brutal civil war just a generation before. The challenge for the new government was to provide a compelling case for national unity whilst also allowing room for regional autonomy.

Spain is not alone in its regional diversity; Italians frequently define themselves by their region rather than by their nation, and even France, one of Europe’s older nations, has separatist wings. But Spain is not marked by many ‘dialects’ as is the Italian case; it is a single country with many languages. The Constitution granted autonomy within a national framework to Spain’s regions, and by the 1990s, it seemed to have achieved the desired results. Surveys in Catalonia, Galicia and the Basque Country showed that an increasing proportion of the population in these areas was now defining itself primarily as ‘Spanish’.

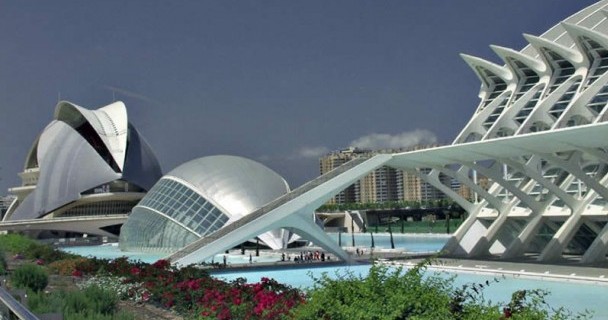

Catalonia, in spite of its central role in the Civil War, had become the most integrated of the traditional separatist regions. There was now room for children to learn Catalan, for flags to be displayed on civic institutions in Barcelona, for the Barcelona football team to play without fear of intimidation. The Olympics of 1992 in the city positioned Barcelona as a fully integrated representative of Spain on a global stage.

Michael Billig’s 1995 theory of ‘banal nationalism’ seemed to find its perfect expression in the region; with a certain amount of autonomy allowed, the region no longer had to fight for independence. By giving Catalonia an inch, Spain ensured that it did not seek to take a mile. Yet Billig’s theory suggests a certain negativity to such developments, as if a blandness, an idle acceptance of the status quo, had set in. In reality, Catalonia’s status as simply one of many regions of Spain ought to be celebrated.

In 1943, Real Madrid beat Barcelona 11-1 in a cup match at the Bernabéu. Barcelona had scored first and were level at the break, before Franco intervened at half-time, threatening the Barca players. A second-half walkover was to follow.

In 1943, Real Madrid beat Barcelona 11-1 in a cup match at the Bernabéu. Barcelona had scored first and were level at the break, before Franco intervened at half-time, threatening the Barca players. A second-half walkover was to follow.

Football in Spain has always been deeply political. To this day, Athletic Bilbao sign only Basque players, and old tensions resurface with every clasico. It would be difficult to explain to any fan in the Nou Camp for the Barcelona-Real Madrid showdown in a few weeks’ time that there is anything ‘banal’ about the rivalry.

Yet it is a rivalry which, in spite of a number of controversial events in recent years, appears to recognise the limits of common decency. The dark days of the 1940s seem a long way off in a time when Real Madrid’s international cohort are led by a man from the opposite side of the Iberian peninsula, whilst Barcelona possess the core of the all-conquering Spanish national team.

The great success story of Spain in the post-Franco years is that the country now appears to have a more developed sense of national identity whilst regional pride remains. In a country where football and politics so often overlap, this has been reflected in the clash between the nation’s two most decorated sides. The rivalry between Barcelona and Real Madrid is no longer pseudo-ethnic, and nor is it overtly ideological: it is simply two of the world’s greatest teams engaging in the game’s greatest rivalry.

_______________________________________________________

We hope you have enjoyed this short introduction to the political and socio-historical background of Spanish football. We will be discussing the subject in more depth in future content and hope to bring a unique and informative look at all aspects of the game in Spain.

Follow @icentrocampista

14 Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment Login

Pingback: Catalonia is not Spain! – Nationalism, separatism and the greatest rivalry in … – El Centrocampista